Jeremy Cowart held the phone, on speaker, out for him and the rest of his production team to hear.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a problem like that ever happening,” the voice from the phone stated flatly.

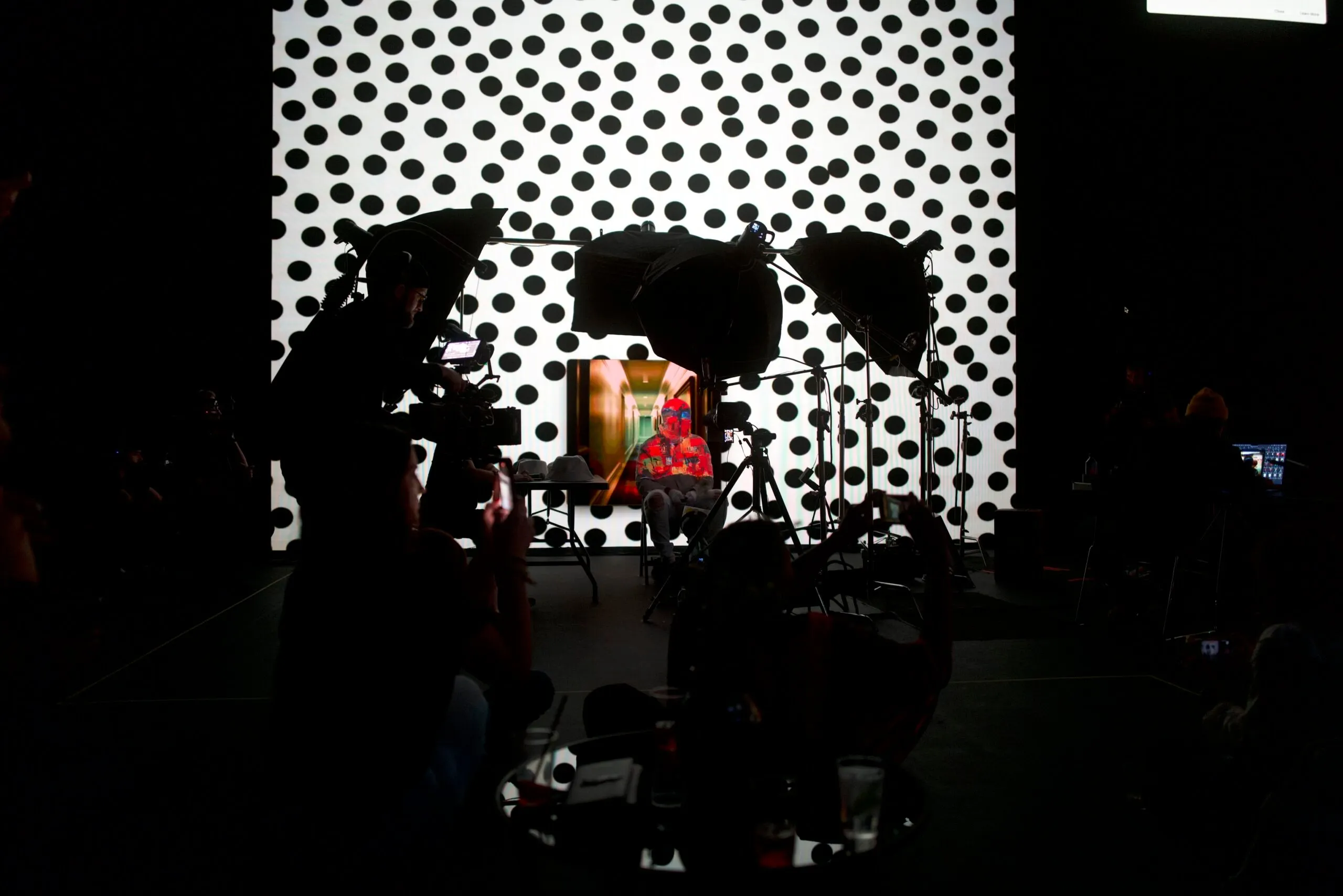

Cowart pursed his lips, but only slightly. In just over six hours, on the massive Nashville studio stage where he currently stood, the photographer would attempt to—before a live audience—create 10,000 unique photo-based self-portrait NFTs.

Each would feature three distinct layers of meticulously-chosen visuals, including prisms and lasers, all flashing rapidly in randomized combinations from multiple lighting sources including the massive, 130-foot LED volume wall looming behind him.

All of the photos were to be edited instantaneously into eight different styles (each distributed at varying and pre-arranged frequencies) via an app custom-created for this single event by the man on the phone, who was either in Finland or a nearby country (Cowart wasn’t sure). And all of this was supposed to happen in about 20 minutes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the MacBook Pro tasked with processing that all in real-time was having a hard time keeping up.

But even that wasn’t the sole concern on Cowart’s mind Tuesday afternoon. The artist planned to be at center of all of these 10,000 photos, in a white bodysuit and mask emblematic of a blank canvas. Every single movement he made during the 20 minutes that those thousands of photos were being taken would impact their appearance and rarity.

“I have to make sure I stay centered, because even if I’m barely off-center, it doesn’t work,” Cowart told Decrypt in Nashville, hours before his “Auras” event was to take place. “Even if I turn my head or angle my head, those are rarity traits.”

Why was Cowart putting these entirely self-created pressures and restraints on himself? There was no practical need for all of the photos to be taken in 20 minutes, nor for them all to be edited instantly—let alone for this entire, mostly untested process to unfold in front of a live audience in real time.

“I’m drawn to big, scary things, to things that are really hard,” Cowart said, shrugging, when asked why he was doing this. “And this has pushed me to my limits in all kinds of different ways. I don’t know. I don’t know if it will work. I think it will.”

Cowart is used to being on a big stage, metaphorically. He has photographed subjects including Barack Obama, Taylor Swift, and the Kardashians, and his work has been regularly featured in Rolling Stone, The New York Times, and Time. Over the course of that career, he has privately experimented with and developed numerous novel photography techniques. “Auras” utilizes many of them, finally showcased to the world in concert.

“This is the culmination of about 10 years of pushing myself in the studio and trying new things,” Cowart said. “Tonight is me revealing all of that for the first time.”

By the late afternoon, the live photo-editing process was still having some problems. So Cowart relented, at least on that one point—the 10,000 photos could be edited in the five minutes following the capturing process, he decided. The audience would still get to see the whole creation process from start to finish, and all in less than 30 minutes.

All of a sudden, it was time. A little over 150 guests—mostly from the Nashville area, but also from across the country—poured into the studio.

After opening remarks, Cowart took the stage, his entire body and face covered in white. Brooding classical music boomed from the darkened ceiling as a cacophony of lights, designs, photos, and faces flashed across Cowart’s body to the cheers of the crowd.

The photos were being taken too quickly for the eye to catch. But on the farther end of the studio’s massive LED wall, a colossal projection of Cowart’s desktop displayed the inflow of raw pictures, about eight per second, each painted with an entirely different combination of images, tones, and light.

The cumulative resulting effect of the performance, which one attendee later described as unexpectedly emotional, was hypnotic, and—in spite of the extreme degree of overstimulation—soothing in its synchronicity.

“The way that Jeremy’s art was flashing, sometimes the [music’s] tempo synced up perfectly,” Cristina Spinei, the composer whose work played over the process, told Decrypt. “I was watching it like ‘Oh my god, we couldn’t have planned this.’”

Spinei, whose music combines classical acoustics with electronic elements, also uses NFTs to release her works. At first, the technology seemed like a more efficient way to control her distribution process. But Spinei’s embrace of the blockchain also had some unexpected repercussions.

“When I first got into Web3, I didn't realize the capacity that it would have to change my music,” she said. “There's this really freeing feeling of being released from a genre. That there's no box an artist has to fit into.”

Watching Cowart bare it all on Tuesday night, the crowd cheering louder and louder as the photo tally steadily ticked towards 10,000, Spinei felt that same liberating spirit of Web3—one focused less on technology, and more on embracing the genuinely weird and new.

“Now there's a proper place for this work, and an audience interested in something a little bit different,” Spinei said. “Ideas and projects that break down the barriers of what visual art is, of what music is.”

Just before 8pm in Nashville, Cowart achieved his dream: his series of 10,000 photos, all unique, had been flawlessly birthed before a crowd of witnesses. In the aftermath, they came up to congratulate him, to shake his hand, to hug him, to toast him—and, not to miss an opportunity, to get their photos taken by him on the “Auras” stage.

“Auras” will mint next week on May 9 on OpenSea, with the project created in partnership with the NFT marketplace and digital creator platform Transient Labs. Current holders of Cowart’s previous NFT project, Block Queens, will be given the opportunity to mint an "Auras" NFT for free.

Cowart envisioned “Auras” as a series of profile picture (PFP) NFTs, meaning those that holders typically display on social media to signal connection to a certain (often elite) online community. Some of the most prominent NFT collections to date, including Bored Ape Yacht Club and CryptoPunks, are also series of 10,000 tokenized PFPs.

Some attendees of Cowart’s event last night, however, pushed back against associating “Auras” with such collections.

I still can’t get over what @jeremycowart did yesterday. Absolute poetry! So cool to be there and watch the process pic.twitter.com/rkH91Lvo7X

— Pain (@CryptoPain7) May 3, 2023

“People are exploiting Web3 at the moment. It's a money-printing machine for a lot of people,” Violetta Zironi, a Nashville-based musician who has minted several NFT collections based on her works, told Decrypt. “When [a series] comes from a businessperson who hires artists to slap together some monkey pictures, that’s speculation. That’s not art.”

To Zironi, proof of a project’s artistic merit lies not in the method in which it is distributed, but in the origin of its creation.

“When there is an artist behind a project, and the idea comes from an artist, and you can see that. That is art,” she said. “This came from Jeremy. This is art.”