Bitcoin mining has never been harder, according to the latest data.

The network’s mining difficulty hit a new all-time high of 37.59 trillion hashes after posting a rare increase of over 10% on January 15, the highest leap since last November—the only time in 2022 when mining difficulty increased by a double-digit percentage.

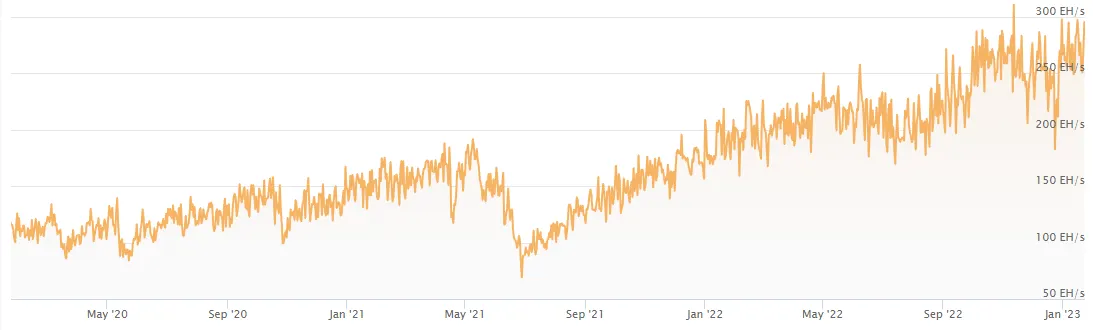

In addition to a high mining difficulty, data from CoinWarz shows that Bitcoin’s hash rate, best understood as the computational power of the network, has also been steadily climbing over the last three years, despite briefly plunging after Terra collapsed in May 2021.

On January 6, 2023, Bitcoin’s hash rate peaked at 361.20 EH/s (ExaHashes per second).

Taken together, both hash rate and mining difficulty indicate a strong and growing network.

At the same time, there have been plenty of recent signs that indicate the mining sector is suffering from serious headwinds.

Compute North, a data center provider for crypto miners and blockchain companies, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last September, while the Nasdaq-listed Bitcoin miner Core Scientific did the same right before Christmas. Mining operation Argo managed to avoid doing so thanks to an end-of-year deal with multi-pronged crypto firm Galaxy Digital.

Several miners have also been dumping their Bitcoin reserves to shore up their balance sheets.

On top of this turmoil, Bitcoin’s hash price, a term coined by mining platform Luxor that measures Bitcoin’s mining revenue potential, is down 43% from its 2022 average. This downturn, coupled with energy price inflation, means that mining margins have never been thinner for some miners.

Still, Bitcoin mining remains a profitable venture for others, and its global reach is only growing.

To separate fact from FUD, Decrypt spoke to some of the sector’s leaders to get a sense of why it's still business as usual in the mining industry, despite sunken Bitcoin prices and widespread insolvencies.

Mining difficulty, hash rate: a quick primer

The Bitcoin network calculates how difficult it is to mine Bitcoin—or how much computational power is required to earn it—every 2,016 blocks (roughly every two weeks)—according to the supply and demand of miners.

The more miners are deployed, the more competition there is among them to confirm a block (and earn the reward), which ultimately makes mining harder and raises its difficulty.

But as difficulty increases, miners can face slimmer profits if Bitcoin’s price doesn’t rise since they’ll need more computing and electricity to mine the same value asset.

However, rising difficulty also indicates a strong and growing network, so it’s impossible to take the temperature of the sector from mining difficulty metrics alone.

Onto hash rate. In simple terms, Bitcoin mining rigs attempt to solve complex encrypted puzzles to validate logs of transactions—called “blocks”—which are then added to Bitcoin’s immutable distributed ledger system. Miners are incentivized to do this via block rewards in the form of Bitcoin.

Each attempt at cracking the encryption generates a unique code called a “hash.” The first miner to transmit the valid hash for their candidate block gets the reward and gets added to the blockchain. In this way, miners are encouraged to validate their blocks quickly.

The higher the hash rate is, the more attempts (or hashes) Bitcoin miners can make within a second to break the code—a clear indicator of the network’s performance.

According to today’s readings, the Bitcoin network is operating at a staggering 273.76 EH/s, meaning miners are making nearly 273 quintillion codebreaking attempts every second.

The state of miners

The economics of mining has a way of separating the wheat from the chaff, experts say.

“The short answer is that most of the over-leveraged miners have already dropped off the network and only the quality and low-cost miners remain,” Scott Norris, co-founder of Bitcoin miner LSJ Ops, told Decrypt. “They have seen many of these bear markets before and have a model that sustained them through it plus a low energy cost. Therefore we aren't seeing the same amount of network drop-off as we have in the past.”

And while troubled operations like Argo and Compute North are making headlines, they haven’t actually switched off any machines yet and are still profiting, albeit with slimmer margins.

Marathon Digital Holdings, the second biggest mining firm in the world by market capitalization, is still increasing its Bitcoin holdings despite the firm’s hefty exposure to Compute North.

Charles Schumacher, VP of Corporate Communications, said: “Obviously we’ve had some hurdles to work through, but all our miners are still running. The site that Compute North used to operate is where actually most of our operational miners are today. That’s now being operated by U.S. Bitcoin Corp and that’s on a wind farm in Texas. There are 68,000 miners there.”

“Because we outsource, we can run pretty lean,” he said, remarking that the total company headcount is “close to 30 people now.” He also attributed Marathon’s resilience to “negotiating contracts and what we’re paying for energy, and a big part of it is the efficiency of our [mining] fleet.”

Marathon has also done a good job of navigating capital markets and raising money at favorable times: “We haven’t been in a position where we were forced to sell Bitcoin. We have signaled to people that our intention is to most likely start selling some to cover operating costs. We wanted to make sure our production was increasing before we started because we don’t wanna have to tap equity markets to pay people’s salaries. That should be funded ideally by the business, and then we would leverage outside capital for growth.”

Marathon is also one of many miners currently deploying rigs that were paid for long in advance. This is a common practice, says Joe Burnett, head analyst at Blockware.

“It can take years to build out mining infrastructure. Some of the infrastructure that came online in 2022 and even early 2023 was funded by capital raised back in 2021,” he told Decrypt. “This is because you can't source energy, build large mining facilities, manufacture, order, and ship mining rigs, and plug them in very fast.”

It's not just mining economics and downtrodden prices that can affect the sector either. Mother nature recently played an unexpected role in the latest volatility too.

A mining difficulty leap of over 10% like the one seen last week, is “relatively very high” said Colin Harper, head of content and research at mining op Luxor.

However, this sizable recent growth spurt was not the result of a sudden mass deployment of hardware. Rather, it was down to a spell of bad weather in North America before Christmas that led to a negative adjustment that was factored back into a sudden upward readjustment.

“When the cold front gripped North America, some miners turned off because the cold caused operational issues while others curtailed their power draw to supply electricity back to the grid in response to power shortages,” said Harper.

When the bad weather ended, however, those miners came back online, lifting hash rate and leading to a hefty jump in the mining difficulty, said Harper.

“The cold snap took 37 EH/s offline—around 14% of Bitcoin's hash rate prior to it—leading to significantly slowed block times and a 3.59% drop in mining difficulty adjustment on January 2. When the bad weather ended, 37 EH/s came back online," he said. "Block times accelerated, causing blocks to get validated more quickly, which led to the upward adjustment we saw on January 15.”

'Someone, Somewhere' will always mine Bitcoin

While Bitcoin may be in a bear market right now, energy isn't.

Between 2021 and 2022, industrial electricity prices ballooned 16% since last year while the price of Bitcoin has almost halved from this time last year.

So, what price would Bitcoin need to be at for mining to stop being profitable? Well, it’s complicated.

“At current levels, a miner that is running an S19j Pro that produces a hash rate of 100 terahashes a second is currently breakeven at $0.096/kWh power costs,” said Harper. “If Bitcoin's price was cut in half from here, that breakeven would then become $0.048/kWh."

Basically, the only way for Bitcoin mining to no longer be profitable is if it were to hit zero.

"Someone, somewhere has power cheap enough to mine BTC even under the most nuclear bearish conditions,” he concluded.

And with Bitcoin hovering around the $23,000 level, it looks like a whole lot of miners are getting back into the game.