In brief

- Bitcoin is nowhere near ready to become the world's default digital payment option.

- An enormous backlog would result if the 700 billion digital transactions a year that take place globally were processed on-chain.

- Several possible scaling solutions are in the works, with the pace of development is slow—but steady.

For the world’s leading cryptocurrency, mass adoption as a form of electronic cash was the original goal. But these days, while Bitcoin’s price has increased, people are more likely to treat it as a store of value. And while we’re seeing a boom in non-cash transactions, merchant payments made in Bitcoin are down. Many users have concluded that it has drawbacks as a way of making purchases, being slower and more expensive (at least for smaller transactions) than traditional cash.

That may not always be the case, though. Some devotees are determined to reach a state where almost all the world’s digital transactions are made in Bitcoin; where crypto wallets are routinely used to buy anything from a lemon to a Lamborghini, and where transactions are quick, and fees are low.

So what, technically, needs to happen for Bitcoin to reach the stage where it’s the predominant currency for peer-to-peer payments around the world?

The opportunity

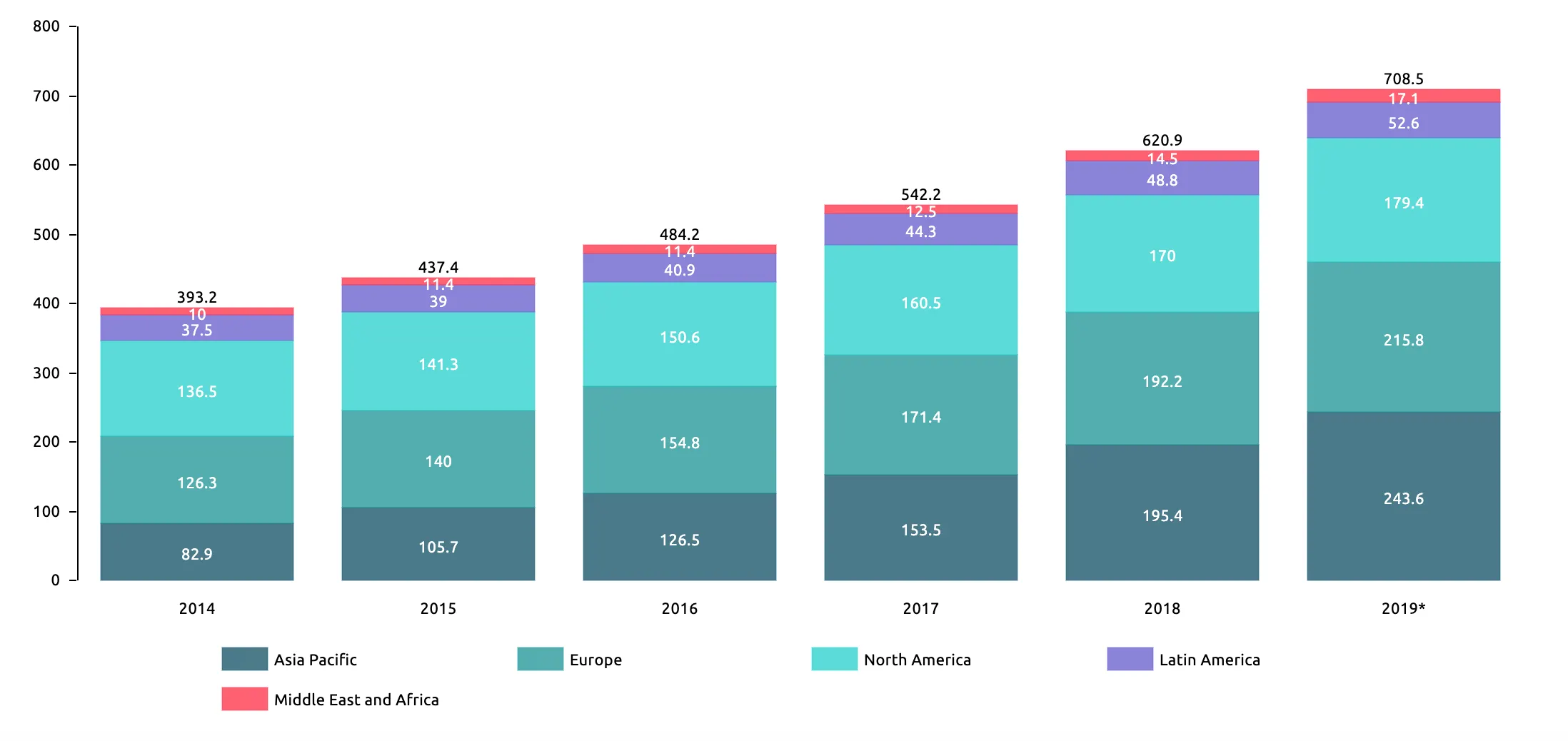

In 2019, approximately 708.5 billion digital transactions were made annually. That amounts to 1.9 billion transactions a day.

To deal with all of these, the Bitcoin blockchain would need to process 13,194,444 transactions every 10 minutes—the rate at which blocks are processed.

To process 13,194,444 transactions every 10 minutes, with a Bitcoin transaction size currently averaging 537 bytes, each block would need to hold just over 7GB of data.

With the entire Bitcoin blockchain totaling just over 300GB as of September 2020, that would be equivalent to adding the entire current Bitcoin blockchain every 43 days.

This transaction volume would generate just over a terabyte of data added to the blockchain every day, or 372 terabytes a year.

The reality

Currently, there’s no way technically to achieve that. Bitcoin’s block size is fixed at 1MB (it can be exceeded— but only slightly.)

And since block time and size are fixed, 13,914,444 transactions would be impossible to process in ten minutes, creating a huge backlog (or mempool, in blockchain parlance.)

How big would the mempool be? Having exhausted our own math, Decrypt asked Jason Deane, an analyst at Quantum Economics.

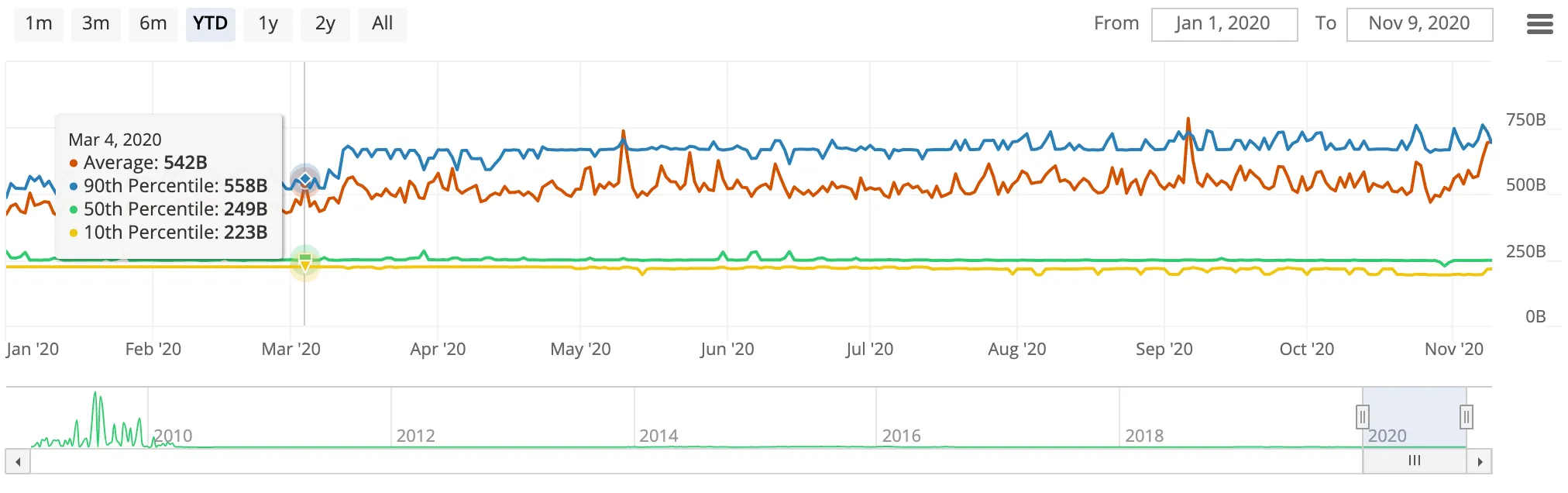

He told us that, based on historical data, the network can manage around 3,333 transactions per 10 min block— that’s roughly 5.5 per second (TPS). For comparison, Visa can process something like 1,700 TPS. But Bitcoin’s tech is still nascent, and 13,914,444 transactions would take 4174.5 blocks and roughly 29 days to clear.

“And that's only one block of data we should be clearing in 10 minutes!” said Deane, who added that the network would back up exponentially. “By the time we completed that batch of transactions, there would also be another 13, 914,444x4,175 transactions to clear or 580,092,803,700 in total.”

Increasing Bitcoin’s block size

To cope with a couple of billion daily transactions on the blockchain itself, Bitcoin would need “a network, hardware, and transfer speeds far in excess to what we have now,” said Deane—and for that reason, solutions based on off-chain transactions, such as “sidechains” exist. “Even if you somehow created a scenario where a 7GB block would work, I’d argue the tech isn't up to it, and there are too many negative implications for that to be desirable,” he added.

One is the argument that it’s impossible to continue to increase the block size indefinitely, and that it will lead to greater centralization. If node operators need to download blocks on the scale of gigabytes, and can’t afford the hardware or Internet costs associated, that could be a roadblock for many. Increased centralization would be a consequence.

Then there are the storage costs of data and the bandwidth for transmitting it all to take into account. “There’s an inherent tradeoff between scale and decentralization when you talk about transactions on the network,” said Bitcoin Core developer Gregory Maxwell in 2014. “You’d need a lot of bandwidth, on the order of a gigabit connection. It would work. The problem is that it wouldn’t be very decentralized, because who is going to run a node?”

But plenty of people argue that increasing block size is key to bringing Bitcoin into mainstream adoption, particularly as other solutions are still a work in progress. It would allow more transactions to be confirmed in each block, and lower fees, making the network faster and cheaper. It’s what the Bitcoin Cash community did, when they forked from Bitcoin core, changing the block size first to 8 MB, and later to 32 MB.

But given that, in practice, the average block on the Bitcoin Cash network is still under 1 MB, the debate on block size—which has raged on for many years—remains unresolved. Instead, other solutions have gained prominence.

Shrinking the amount of data used in each transaction

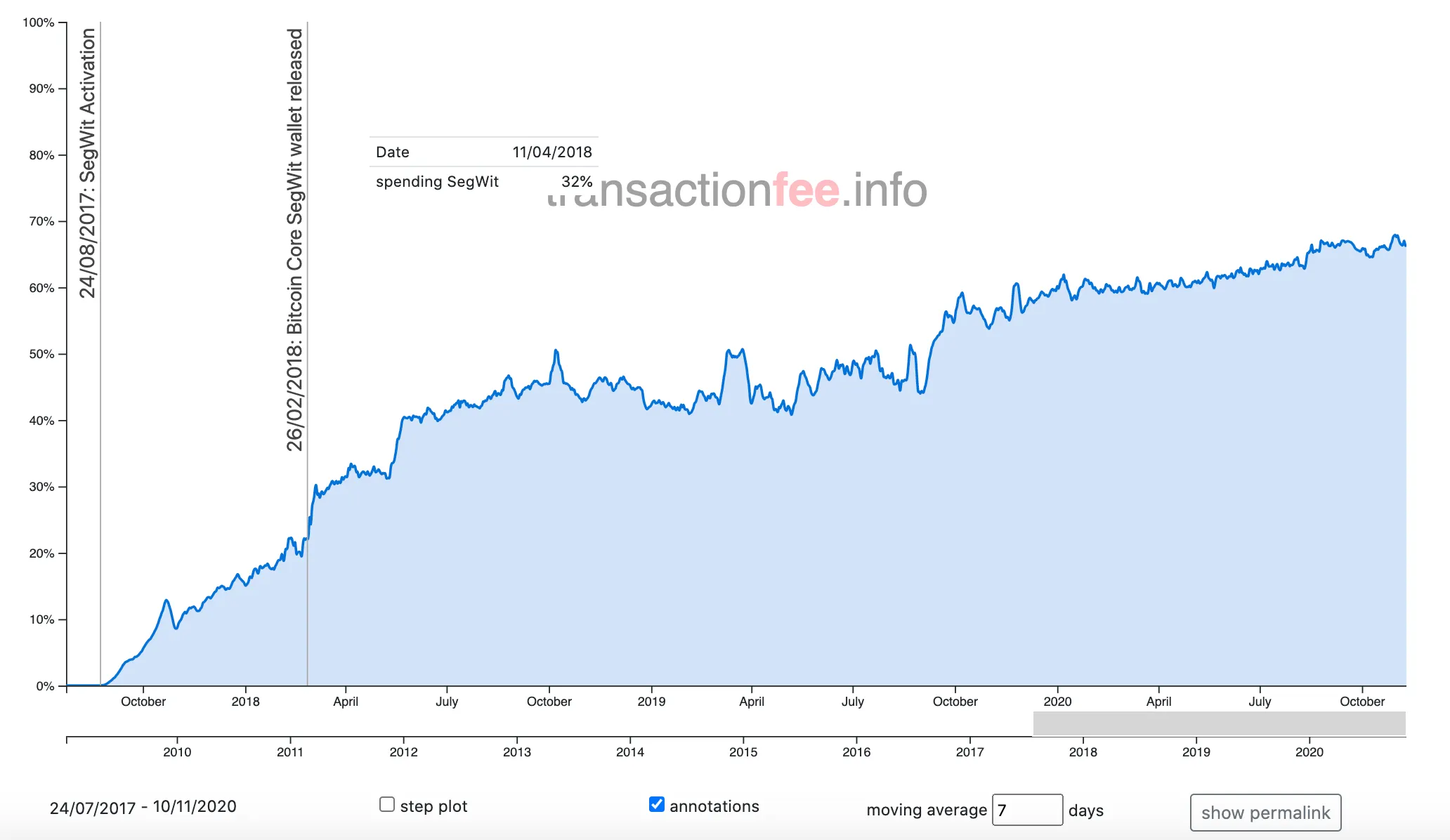

This would mean more transactions can fit into a block, and is akin to what Bitcoin achieved with its 2017 Segregated Witness update, known as SegWit, which improved overall network capacity.

SegWit allows Bitcoin blocks, to expand, if necessary, from 1MB to 4 MB, increasing the number of transactions that can be processed per second by the network. That means fees are lower, too, and SegWit is now reaching over 60% of Bitcoin transactions.

The Lightning Network

So-called “second-layer solutions” sit on top of the Bitcoin blockchain. The best-known is the Lightning Network. It works by allowing nodes to open up channels, and transact between themselves, transmitting the final tally to be recorded on the Bitcoin blockchain, and making for a—potentially—faster, cheaper payment system.

Lightning is still a work in progress, with technical issues that need to be ironed out, but developers are making headway, and new features and improvements are constantly emerging.

Sidechains

Sidechains are blockchains that branch off the Bitcoin blockchain and are able to move assets between themselves, freeing up bandwidth for things that need to be settled on the main chain.

Blockstream’s Liquid Network is an example. The downside is that each sidechain needs to be secured by nodes, which can lead to issues with trust and security.

Sharding

Sharding is one of the most popular methods employed by other blockchains to ensure scalability—it’s one of the key features of the impending Ethereum 2.0 upgrade, for example.

It involves breaking transactions up into “shards,” with nodes effectively performing parallel processing to speed up the system, enabling speeds of 100,000 transactions per second (as Ethereum 2.0 hopes to demonstrate). But the process adds complexity and may be detrimental for security because sharding could increase the chances of a “double-spend” as a result of an attack.

Both because of the technical challenges involved, and the general reluctance of Bitcoin devs to plunge into uncharted waters, it’s unlikely that sharding will be developed as a scalability solution for Bitcoin any time soon.

A measured approach

Bitcoin’s limitations are plain for all to see. The prospect of the blockchain processing 700 billion transactions, annually, is nowhere near a reality. Scaling solutions, like sidechains and the Lightning Network, are helping, but there are drawbacks, and there isn’t necessarily a clear, winning approach.

Ultimately, ensuring the Bitcoin blockchain’s security remains a priority, and more than one solution could end up being used in tandem. Quantum computing could play a part too.

Meanwhile, experimentation continues every day, with developers getting ever closer to improving Bitcoin’s scalability. Just don’t expect it to be too soon.