In brief

- Cash use is in decline, a trend that has been accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic.

- Advocates for physical cash argue that the demise of physical cash risks leaving vulnerable members of the population behind.

- A UCL study suggests that CBDCs will need to replicate the privacy and anonymity of physical cash to achieve widespread acceptance.

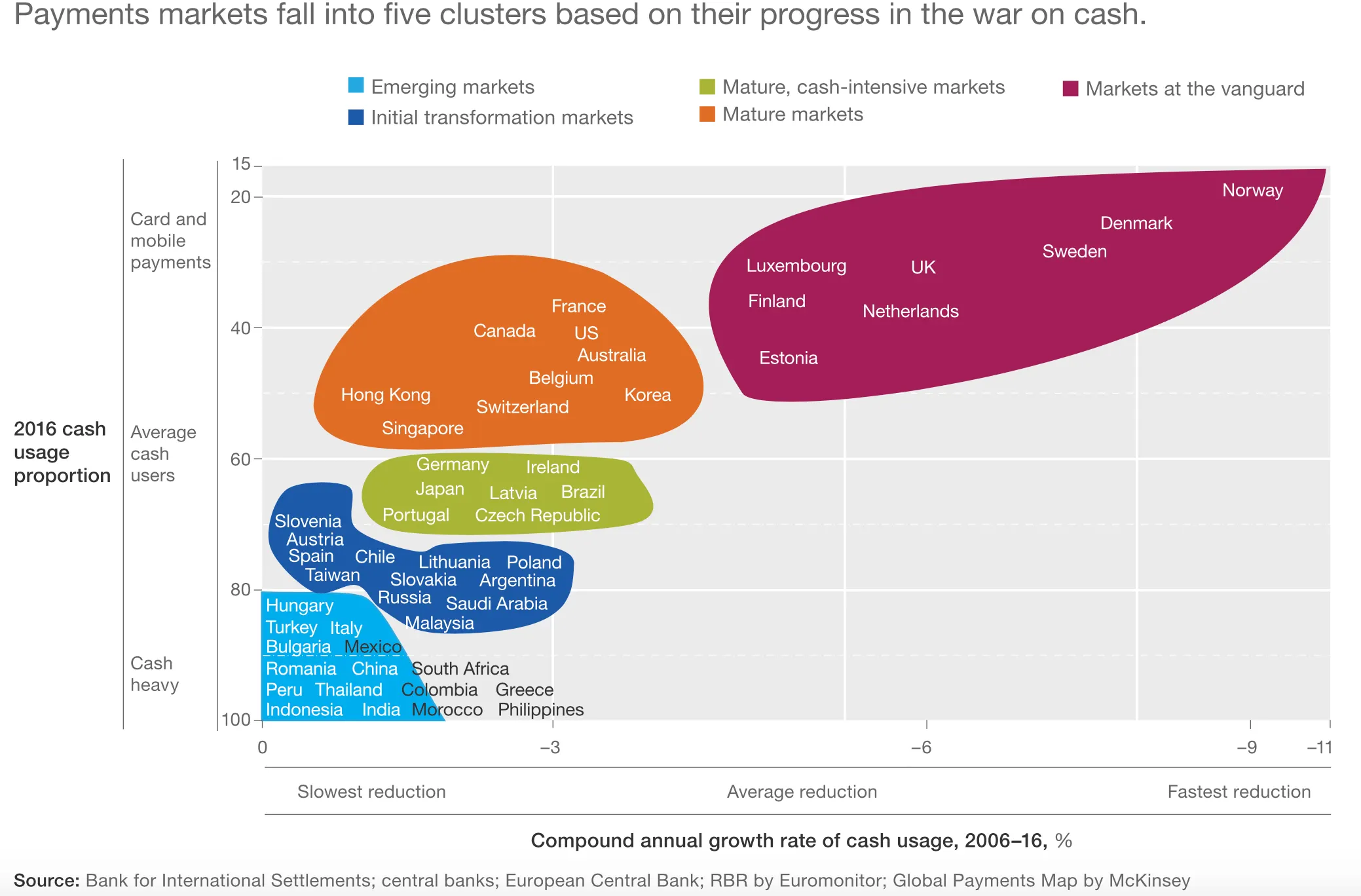

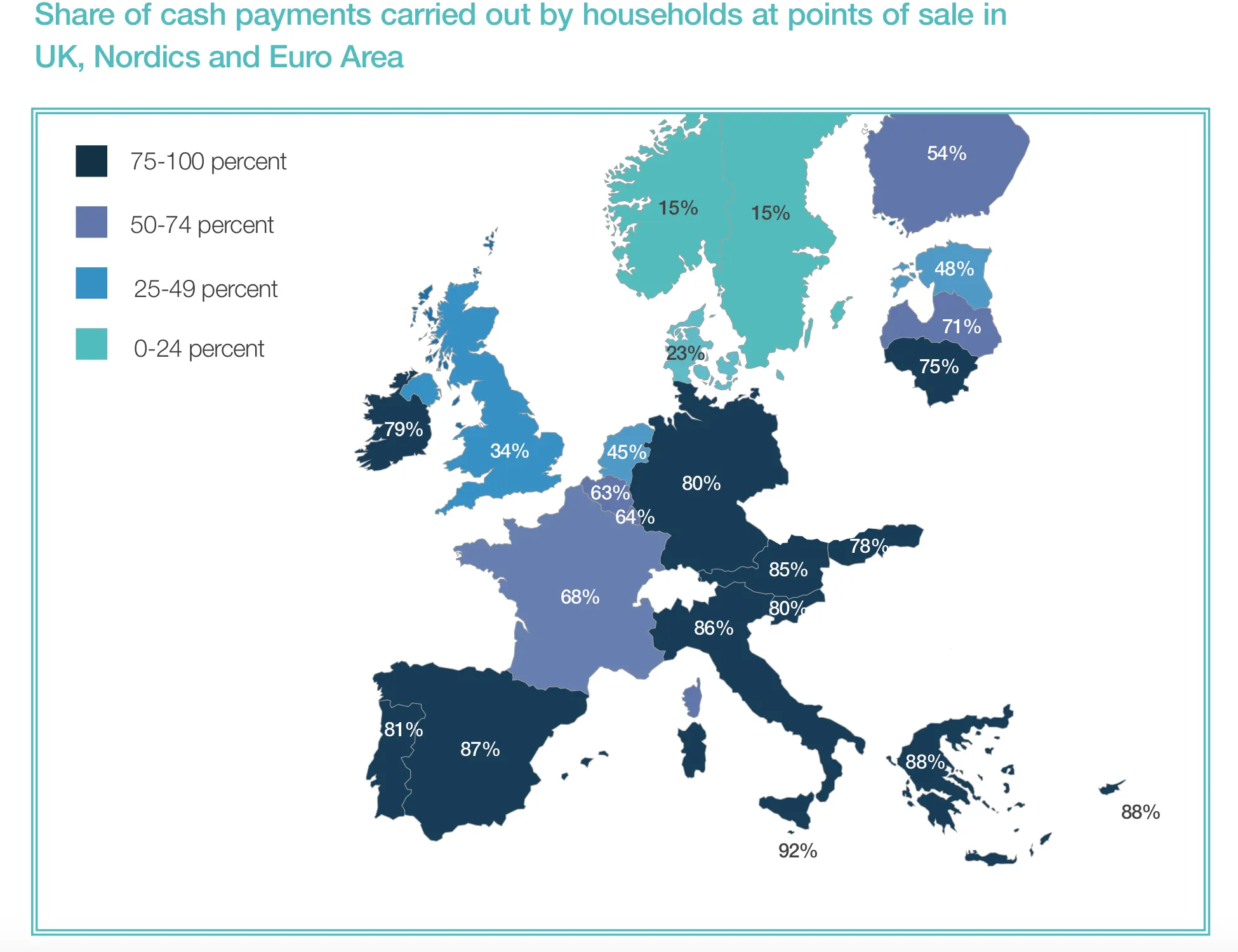

Cash is no longer king. Across Europe, the use of physical cash is predicted to fall by an average of 30% in 2020 as consumers switch to digital payments and contactless cards, mirroring long-term trends in the US.

The global coronavirus pandemic has only accelerated cash’s decline. Despite the WHO stating that it doesn’t regard cash as a vector for infection, a fifth of Britons has tried “laundering their money” in disinfectant amidst concerns about it spreading Covid-19. The average Brit has gone without using cash for 44 days, and many have found they don’t miss it as much as they’d expected.

Championed by the young, payment apps like Apple Pay, Square’s CashApp and PayPal affiliate Venmo have achieved widespread adoption amidst the pandemic. Last week, Visa predicted a “permanent” shift away from cash.

Meanwhile, central banks are racing to create digital currencies, while struggling with the seemingly contradictory demands of privacy and security. Some worry about leaving the vulnerable behind; others think cryptocurrencies may be the answer.

The online marketplace

Florence Road Market is an open-air farmer’s market, in the heart of trendy, health-conscious Brighton, on the UK’s southern shores. It sells everything from artisan loaves and cinnamon buns to world-beating strawberries, organic vegetables, meat, and cheese.

It’s one of many businesses that’s had to move online in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, setting up an online ordering service using an off-the-shelf tool from payments company Square.

“The wild thing for us about going to purely electronic payments is that Florence Road Market was set up to be a deliberately analog space—a friendly neighborhood market where personal relationships are the main thing,” said Ben Szobody, Projects Development Manager for One Church Brighton, the charity that runs the market.

But the new online-only business, with curbside collections and delivery options, has seen its profits increase six times over. Vendors are not in a hurry to set up their stalls again—they’ve gained new customers and found that old ones are enthusiastic about shopping online.

The bonkers response to our farmers market in a box has been awesome. Now we’re making it affordable/free to families in need. This weekend, pre-order your box +1 for someone else. We’ll distribute via @chompbrighton. Help us out, eh? https://t.co/kGXLR6fL9l pic.twitter.com/FJQ3Z1nvzA

— Florence Road Market (@FloRoadMarket) March 20, 2020

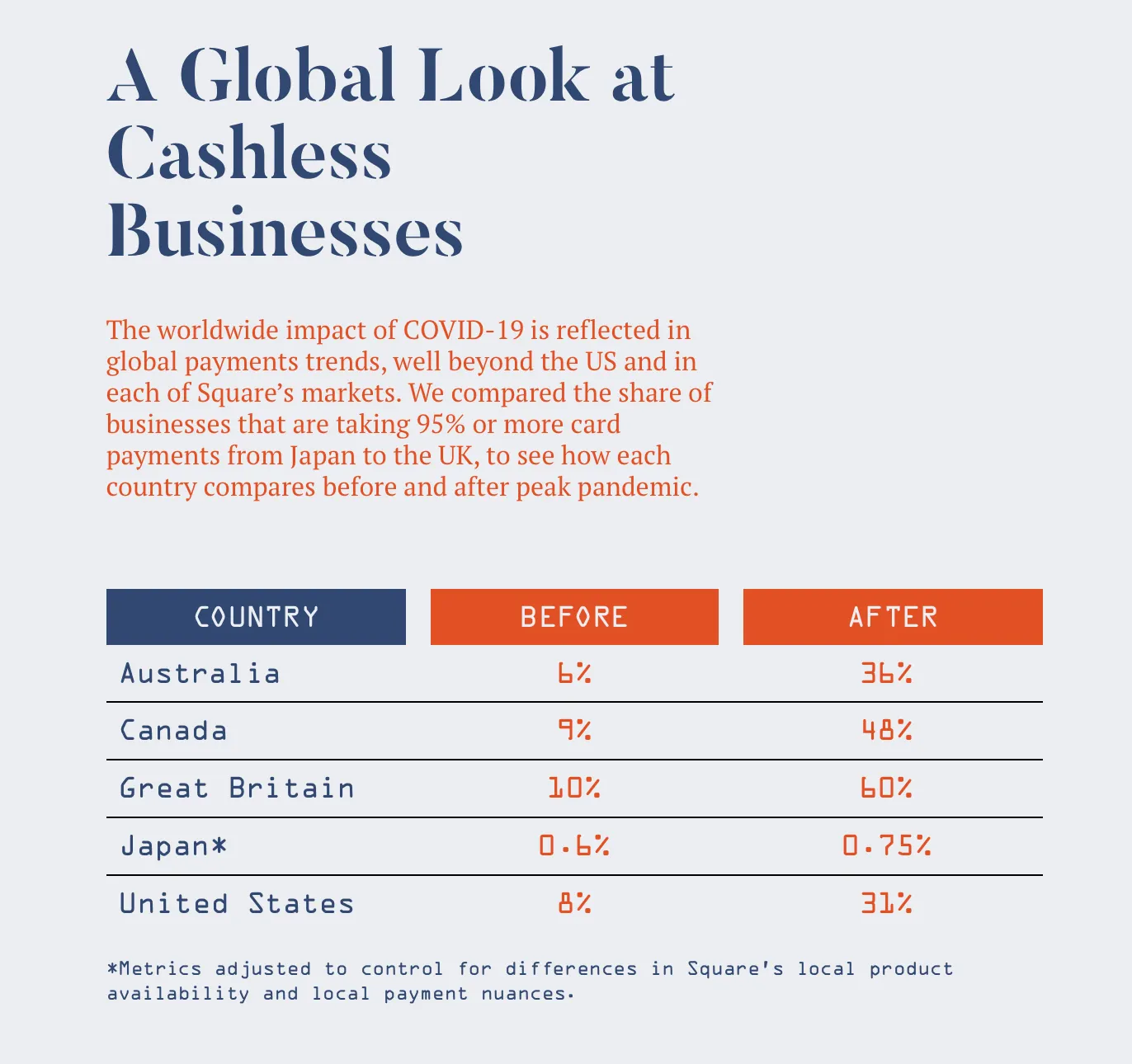

It’s a trend mirrored around the globe, according to Square; its own data shows that the share of businesses taking 95% or more in card payments is skyrocketing. A Square UK spokesperson told Decrypt that the company has seen a big uptick in businesses moving online, or bolstering their presence on existing online platforms.

The danger of going over a cashless precipice

It’s possible to use online payment services like Square and PayPal without a bank account, by transferring funds to a prepaid debit card. But the majority of payment services are designed around having access to a bank account, a smartphone, and broadband—which threatens to exclude 8.5 million in the USA alone. Yet the means of accessing cash are disappearing before our eyes.

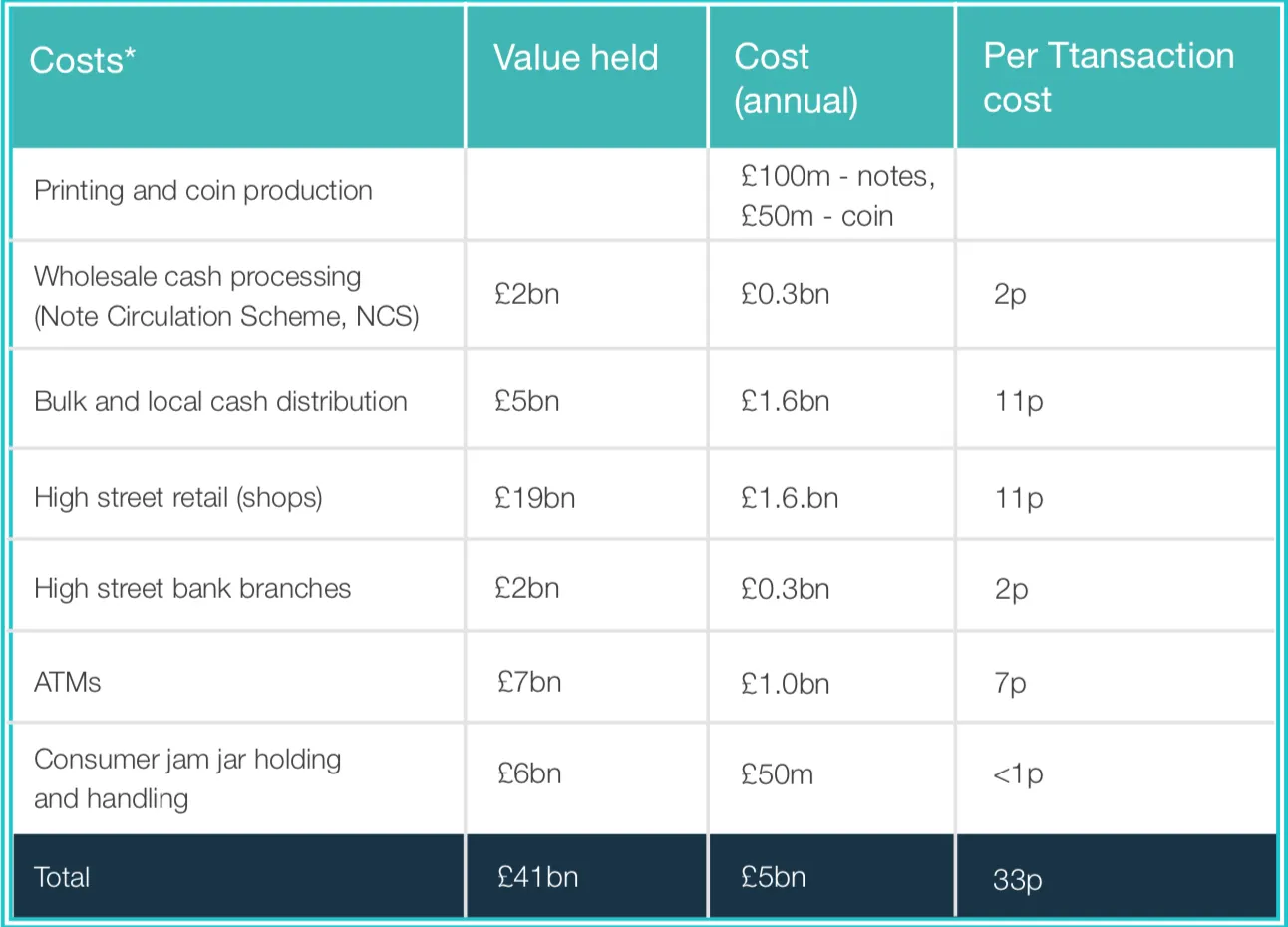

In the UK alone, it costs around £5 billion a year ($6 billion) to run the network of ATMs, delivery, warehousing, and printing services needed to support a cash economy. In the face of falling demand, that’s looking unsustainable, and banks are axing branches and ATM facilities, while merchants are increasingly reluctant to meet the rising costs of offering cash payments.

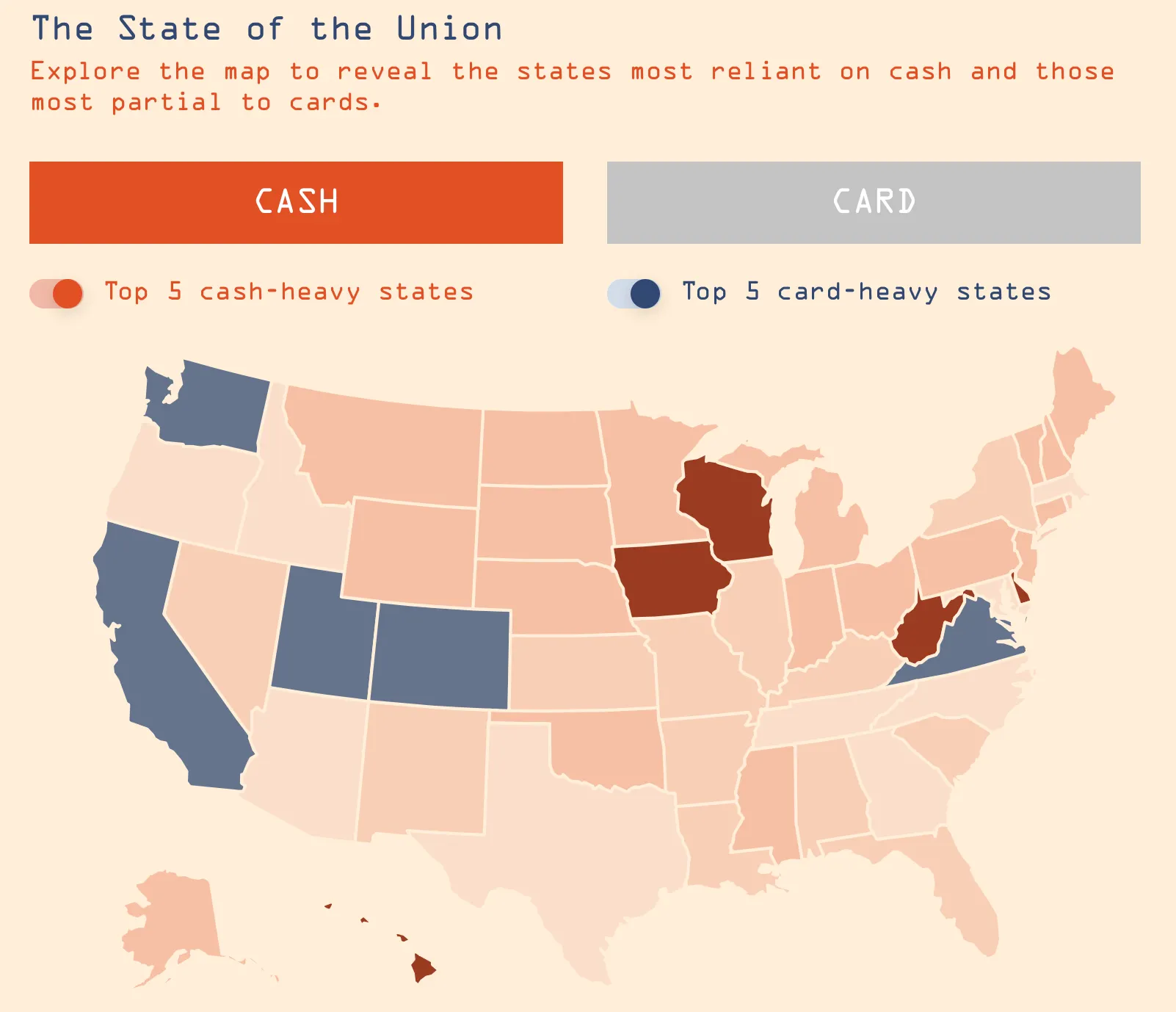

Of course, some parts of the world are still reliant on cash—90% of Mexicans preferred to use cash for transactions in 2018. In India, the cash share compared to the country's $3 trillion GDP was 49.3% in 2019.

But most banks and financial firms have an interest in phasing out cash; they claim it would mean lower crime and higher tax revenues, and they deter customers from using cash with hefty fees.

In Sweden, efforts to bring the grey economy into the formal economy include tax breaks and promotion of peer-to-peer payment technology, but many still rely on cash. Sweden’s government has recently put the brakes on going cashless, for fear of moving too fast. The UK has vowed to protect access to cash, and in the US, states are already beginning to legislate against cashless retail.

A war on cash, or on people who use cash?

Cash advocate and author Brett Scott is concerned that every time a bank closes an ATM, it makes it more difficult to exit the financial webs spun by institutions. “What we call a 'cashless society' is actually a 'bankful society' in which banks get between our every transaction, enabling them to harvest huge amounts of data and increase their stranglehold over our economic lives,” he told Decrypt. The biggest check on banks is the danger of leaving them, he believes.

In the UK, the Access to Cash Review called on the Government, regulators, and banks to take urgent action—with more innovative access to cash access, more inclusive technology and a re-engineered, more sustainable, cash infrastructure—or risk leaving millions (17% of the UK population) behind.

The Review predicts that cash could fall to just 10% of all payments in the next 15 years. Natalie Ceeney, a former civil servant and banker who led the review into the future of cash last year, believes that the coronavirus pandemic may have accelerated the demise of cash by a decade.

The shift towards digital payments, she argued, is an unstoppable force, and could affect the most vulnerable citizens—such as the homeless, or those without the legal immigration status needed to open a bank account.

"For some businesses, where the majority of their customers pay using card or by digital, going cashless is logical,” Ceeney said. But that doesn’t work for everyone. “Not everyone has decent broadband or mobile coverage, or even access to a bank account,” she pointed out. “In fact, for around 20% of the UK population, cash is still a necessity. And what happens when payment systems fail? What's the backup solution?"

The Access to Cash Review calls for more initiatives to protect the vulnerable, such as enabling digital payments using QR codes for vendors of the Big Issue, a newspaper sold by the homeless.

A digital dollar as mighty as the greenback

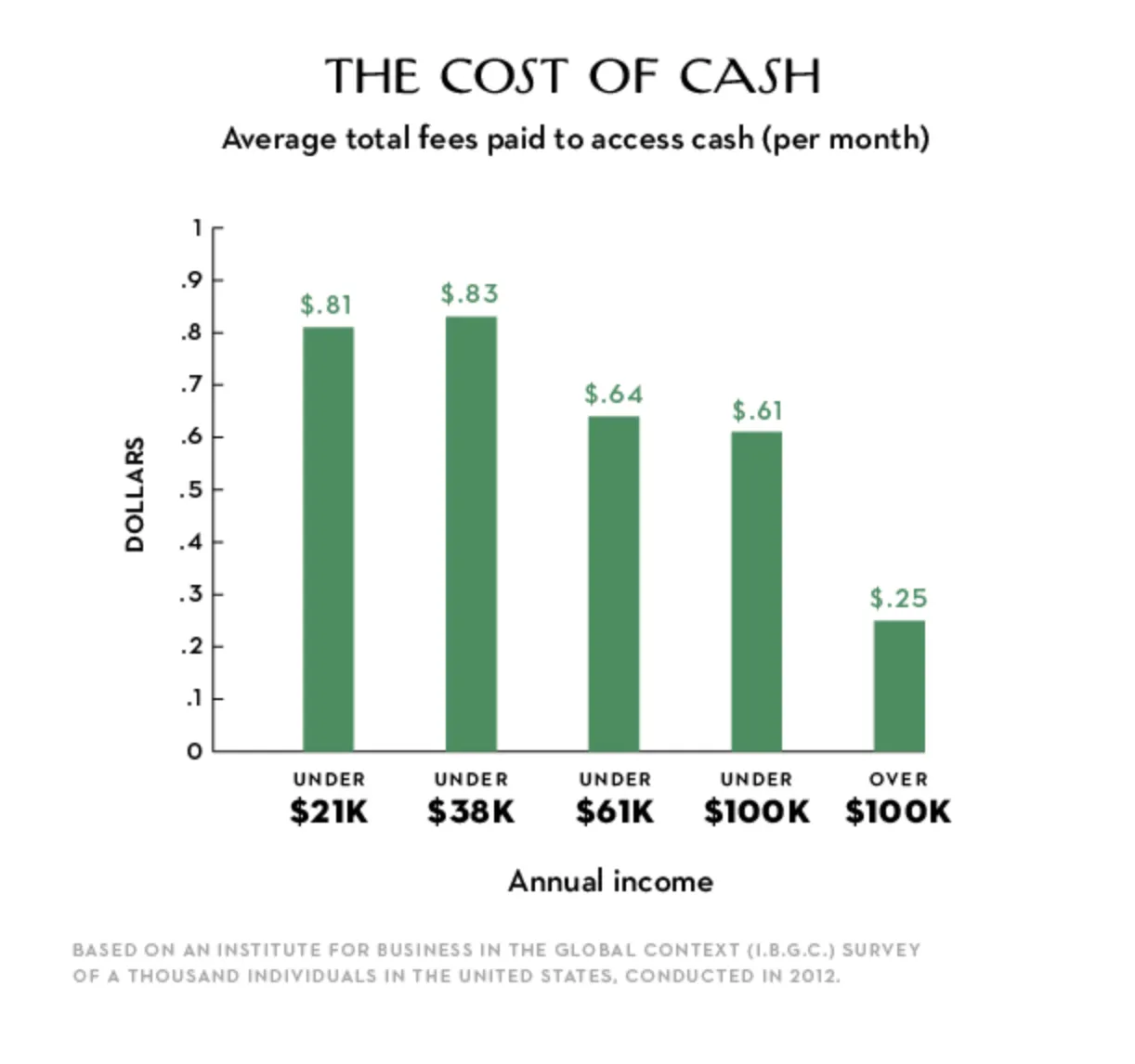

The cost of using cash also disproportionately affects the unbanked. They pay higher fees for cash access and spend more time accessing services.

The need to protect vulnerable unbanked Americans from being left behind during the digital transformation of global finance has renewed calls for a “digital dollar.” Such a scheme would provide people with simple online accounts and make it easier to distribute government stimulus checks—or even a universal basic income.

Chris Giancarlo, former Chairman of the US Commodities and Futures Trading Commission, said earlier this month that any digital dollar should function exactly the same as physical cash, with all the privacy and portability that entails.

But not everyone thinks a digital dollar is such a great idea, John Berlau, a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, has warned that Federal Reserve involvement could hamper private-sector efforts to improve financial inclusion through innovation in cryptocurrency and payments technology.

There are also fears that digital currencies would sacrifice privacy; around 60% of people believe a cashless society would have less privacy, and 74% think it would mean more vulnerability to cyberattacks.

Central bank digital currencies (CBDC,) could allay consumers' privacy and security concerns about trusting their data to big tech—but many don’t trust the banks either. They point to China’s CBDC, which will enable the state to screen every transaction and freeze funds at will.

A recent study from University College London offers some hope; it claims that CBDC anonymity can be achieved without relinquishing control. The study’s author Geoffrey Goodell argues that CBDCs incorporating privacy by design will be seen as “more free and business-friendly than those that rely upon data protection by third parties.”

But the study’s supervisor, Paolo Tasca, argues that CBDCs won’t be a substitute for cash, but will instead be a “hybrid solution between deposits and cash.”

Where does that leave crypto?

The elephant in the room is, of course, cryptocurrency. Advocates claim that cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin don’t require their users to trust any institution or sacrifice their privacy.

But critics point to low rates of adoption, volatility, and the preponderance of hacks. “Crypto-tokens have 'cash-like' qualities in the sense that they are 'digital bearer instruments', but they still fail to be treated as money by the vast majority of people,’ said Brett Scott, “There is a long way to go before crypto has any chance of solving the problem of banks taking over the monetary system.”

The success of Florence Road Market tells a more positive story. Its “Buy one, give one” food box model is now central to a citywide effort to build a more durable, local food network. “This is definitely a digital-native feature that wouldn’t really be possible in an analog environment,” said Szobody. Buoyed by their success, One Church Brighton is now open to other forms of digital payment, said Szobody—and that includes crypto.