When a large institution like the cryptocurrency exchange FTX implodes, it drags others down with it.

That dynamic is what’s referred to in finance as contagion, or the tendency for a financial crisis to spread to other institutions, markets, and regions.

Since FTX filed for bankruptcy on November 11, there’s been a growing list of other companies that have had to disclose their “exposure” to FTX and its related companies FTX US and Alameda Research. In this case, having exposure means a company lent money to, received commitments from, invested in, or had funds deposited with FTX.

For example, Genesis Trading said on November 10 that its trading desk has $175 million in “locked funds” in its FTX trading account. The company later had to suspend withdrawals from its lending arm, citing “unprecendented market turmoil.”

On the same day, crypto exchange and stablecoin issuer Gemini announced withdrawals from its Earn product may be delayed, a knock-on effect of Genesis, the lending partner for Gemini Earn, suspending withdrawals. That was one day after Gemini initially said it had no exposure to FTX—it turned out it did have exposure to Genesis, and Genesis had exposure to FTX.

As a side effect of Gemini’s news, traders on decentralized finance lending protocol Aave were lining up to short Gemini Dollar, GUSD, in anticipation that the firm might become another victim of the FTX contagion.

Now there’s on-chain data that suggests the events leading up to FTX’s collapse were originally triggered by the Terraform Labs collapse, which happened in May 2022.

That would mean, as is often the case, that one source of financial contagion, FTX, links back to another epicenter of contagion, the algorithmic TerraUSD losing its 1:1 peg with the U.S. dollar and wiping out $40 billion in a matter of days.

After TerraUSD collapsed, the resulting contagion led to hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, lender Celsius Network, and crypto broker Voyager Digital to file for bankruptcy over the next two months.

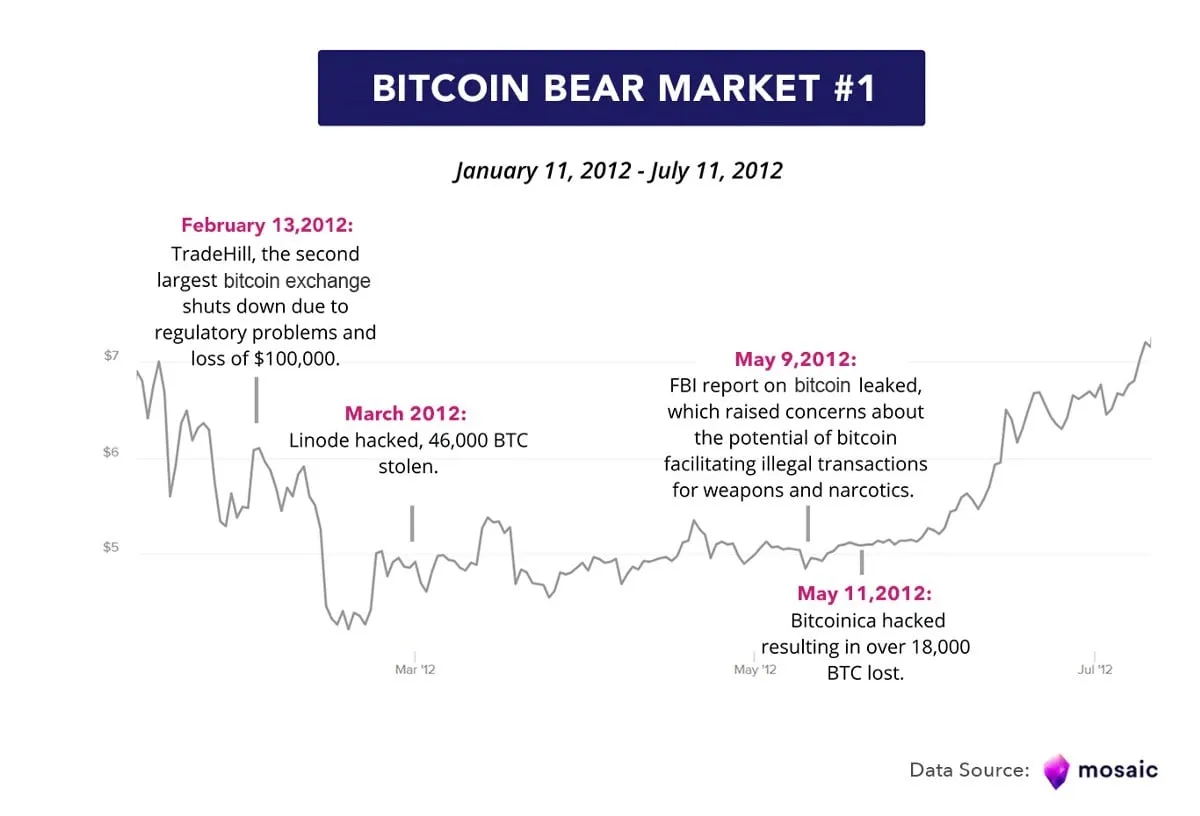

Even before Terra and FTX, there have been other examples of contagion working its way through crypto markets.

In 2013, the FBI shut down the Silk Road, a dark web marketplace that was accessible through the Tor privacy browser, and arrested Ross Ulbrecht. Buyers and sellers used bitcoin for transactions, because it afforded them more anonymity than using fiat.

As a chart from crypto data and research firm Mosaic shows, Silk Road being shut down preceded a 96,000 Bitcoin hack from another darknet marketplace, Sheep Marketplace; China’s Central Bank banning institutions from processing BTC transactions; BitInstant CEO Charlie Shrem was sentenced to prison for running an exchange; and, finally, in February 2014, 850,000 BTC was stolen from crypto exchange Mt. Gox.

In terms of magnitude, Mt. Gox still looms large in the crypto space.

At the time of the hack, the exchange accounted for 70% of all Bitcoin trading volume. It’d been operating since 2010 and experienced a few hacks, including 80,000 BTC being stolen in 2011. But the company abruptly ceased operations when 840,000 BTC—740,000 from customers and the rest from the company—was stolen in 2014.

Leading up to the hack, the Bitcoin price hit an all-time high of $1,000 in November 2013—around the time when Silk Road founder Ulbricht was arrested. But two months after Mt. Gox shuttered, the price of BTC had plummeted to $360 and sent a chill through the market.

Coinbase, at the time a fledgling crypto exchange, published a joint statement condemning the “tragic violation of the trust of users,” with Kraken, Bitstamp, Blockchain.info (which would later become Blockchain.com), Circle and BTC China (which later changed its name to BTCC).

Ironically enough, their statement describes exactly the kind of shady accounting practices that have since come to light in the FTX collapse: “Acting as a custodian should require a high-bar, including appropriate security safeguards that are independently audited and tested on a regular basis, adequate balance sheets and reserves as commercial entities, transparent and accountable customer disclosures, and clear policies to not use customer assets for proprietary trading or for margin loans in leveraged trading.”

The origin of ‘contagion’

Contagion isn’t just a term coined by the crypto industry, although it’s certainly gotten a lot of play during the current brutal bear market.

In the broader context of economics, “contagion” describes the way a crisis starts at one institution, market, or region and then spreads to others.

The phrase has repeatedly been used to describe the crypto ecosystem in 2022, but that’s not where the term originated.

The word itself comes from epidemiology, the branch of medicine focused on the spread of disease. For example, public health experts have been laser focused on stopping the COVID-19 contagion since the start of the pandemic in 2020.

Economists started using the word “contagion” after Thailand’s currency, the baht, collapsed in July 1997 in what’s now referred to as the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. The resulting financial crisis spread through East Asia to Russia and eventually South America.

In brief:

- Contagion is the real or perceived spread of an averse crypto event from one company to another

- Examples of contagion include the consequences of the FTX crash and the Silk Road fiasco