If you’ve been reading our weekly Decrypting DeFi newsletter, you’ve already read a bit about the “Curve Wars," a battle for “deep liquidity” in DeFi.

That discussion has hit a critical mass again recently, and now everyone on Crypto Twitter is again talking about it.

Here's the quick-and-dirty down low, plus how the Curve Wars will inevitably become just DeFi Wars.

The Curve Wars are ultimately a fight for deep liquidity, meaning projects want control over markets that have a high volume of trades between many buyers and sellers. And Curve, a blue-chip DeFi protocol that’s optimized for swapping like-pegged assets (i.e. USDT for USDC, WBTC for RenBTC), is one of the most liquid markets in crypto.

In terms of sheer total value locked (TVL), it is the de-facto largest project, commanding more than $23 billion. (TVL measures all the money that has been deposited in a protocol). For reference, MakerDAO and Aave have TVLs of $18 billion and $14 billion, respectively.

Liquidity, or how much volume there is for a specific asset, is important for a few reasons. One of those reasons is that if liquidity for a token (or a token pair) is low, it means that when you try to buy or sell that token, you’ll encounter slippage. This financial term refers to the difference between the price at which you want to buy or sell an asset and the price you ultimately end up getting. Low liquidity usually means that the difference could be quite large.

This relationship between liquidity and slippage is particularly cumbersome for folks holding large amounts of crypto.

Even if you’re dealing in a relatively liquid asset like a stablecoin, if you decide to move enough of it, you’ll face slippage risk. And though slippage may just be pennies for crypto minnows, whales attempting to move hundreds of millions could end up losing big.

This is even more of a risk when managing a protocol’s treasury. Imagine losing millions in treasury funds because of slippage.

Optimizing for this risk is Curve’s bread and butter.

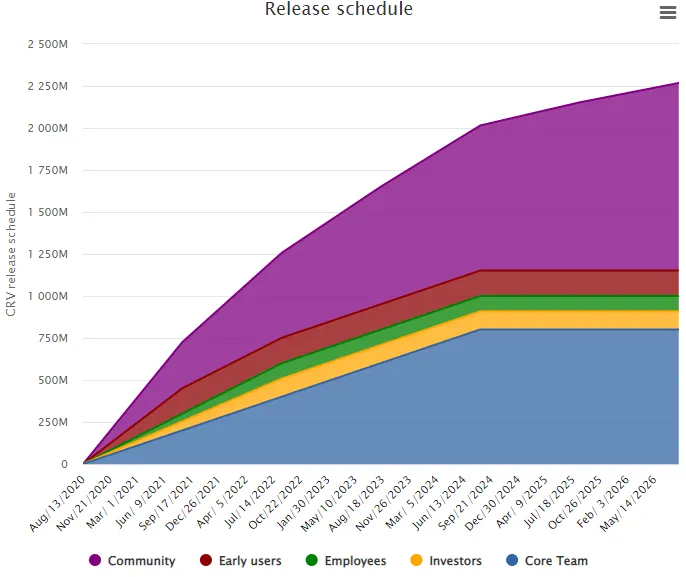

There’s another unique feature about Curve, specifically related to the protocol’s native token CRV. You can get this token by buying it on an exchange or by adding your liquidity to any one of the various Curve pools. The token has a total capped supply of 3.03 billion, after which no more CRV will exist. Like Bitcoin, the rate at which the CRV supply is also distributed will decrease over time.

Holding this token gives you access to voting on various proposals, liquidity gauges (more on that shortly), and lets you earn trading fees.

The only thing you need to do to get access to these benefits is to “vote lock” the CRV token. When you lock this token up, you get a voting token in return called veCRV. The more CRV you lock up, and the longer you lock it up for, the more voting power (veCRV) you get.

That’s CRV’s tokenomics in a nutshell. And other protocols are following Curve's lead.

Yearn Finance, for example, has just passed a proposal that would turn YFI into a vote-locking token. Only those who hold veYFI will be able to decide what happens to the protocol. That same proposal has also introduced similar incentives for gathering votes to create enticing pools on Yearn a la Curve.

Finally, here’s why this is creating a war on Curve, specifically around those “liquidity gauges” mentioned above. Liquidity gauge is a fancy crypto term for defining how much of those CRV rewards an LP can earn when providing liquidity to a Curve pool. The higher the gauge, the more CRV can be earned.

At the moment, for example, the pool for Magic Internet Money, an algorithmic stablecoin pegged to the dollar, has a rather high gauge that users can earn up to 12.85% additional APY paid out in CRV tokens.

Thus, if you have enough voting power (i.e. you’re holding tons of veCRV tokens) you can vote to have your pool earn really high CRV rewards (of which, as mentioned, there is only a fixed amount).

Control the votes, collect more tokens. That’s the game.

Decrypting DeFi is our weekly DeFi newsletter, always led by this essay. Subscribers to our emails get to read the essay first, the day before it goes on our site. Subscribe here.