In brief

- Survey respondents on a recent IMF poll said CBDCs could not be classified as "money."

- The IMF pointed out its own reservations with the prospects of CBDCs.

- However, countries like China are on track to roll out their own CBDCs within the next few years.

A Twitter survey by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Sunday saw the financial regulator and watchdog ask its 1.7 million followers: Are central bank digital currencies [CBDCs] really money?

The answer was one sided. Nearly 65% of the 30,800 respondents, as of Monday morning, voted a clear “no.” The comments were mainly from crypto evangelists (meaning the data may be biased), with some popular influencers even stating that such currencies were scams.

Are central bank digital currencies really money? #poll

— IMF (@IMFNews) January 17, 2021

CBDCs are centralized, digital versions of fiat money. They are similar to stablecoins, which are pegged on a 1:1 basis with a particular fiat currency. Only China has officially issued their own digital currency so far.

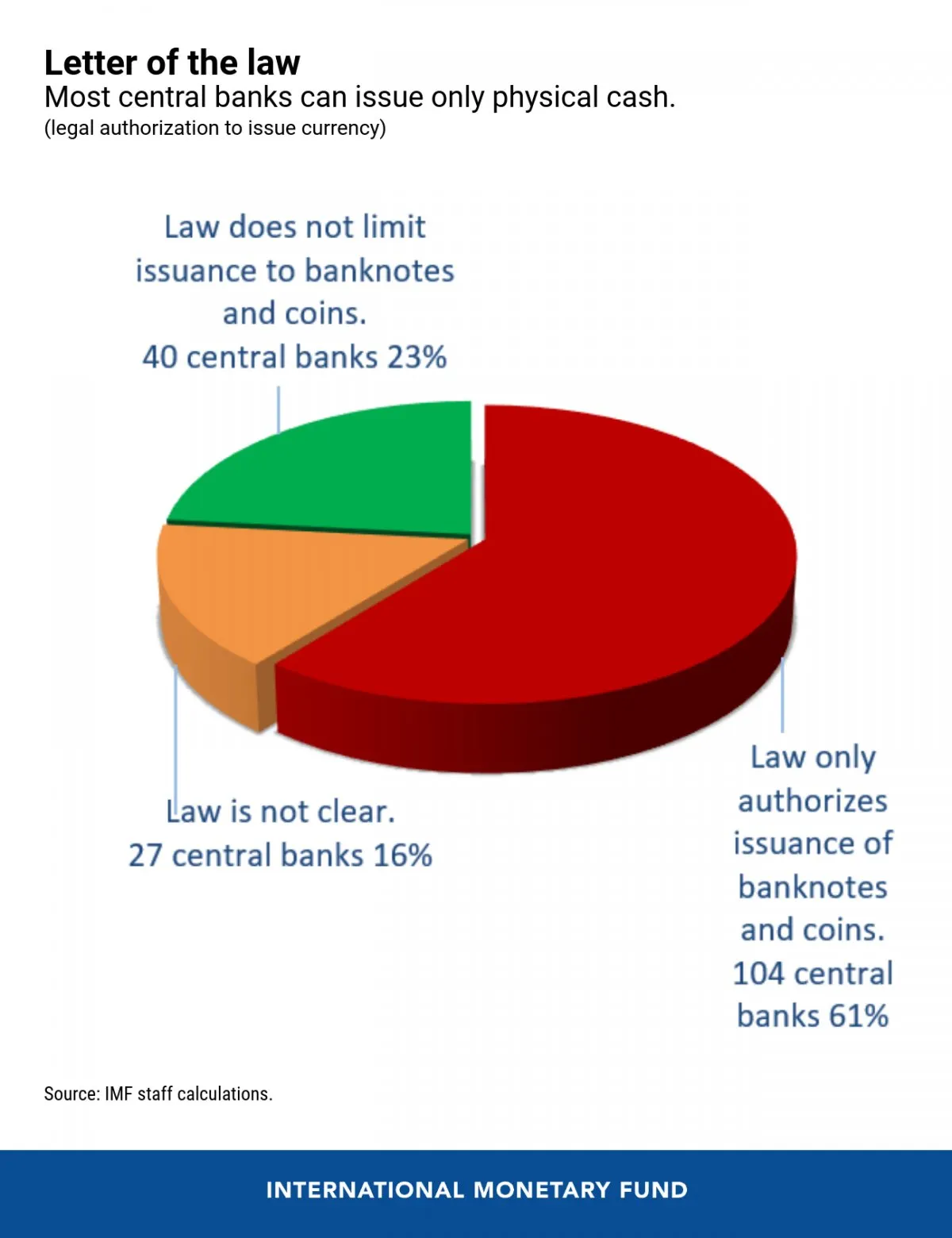

In the same Twitter poll, the IMF added that central banks would face regulatory headwinds while issuing their digital currencies. “While central banks examine the case for developing a digital currency, many might not be allowed to do so by their own by-laws,” the IMF said, adding that 80% of the world’s central banks were authorized to only issue “physical” cash.

As shown in the below image, only 40 countries have laws to issue digital currencies, while the framework for such advancements is “not clear” in 27 countries.

However, what separates paper money from digital money? As per the IMF, all citizens should be able to easily access financial services, and in the case of digital currencies, they must necessarily have digital means (like mobile phones, laptops, internet, etc.) to access such services.

And since the ownership of these devices cannot be imposed by any government—the issuance of digital currency becomes a significant legal issue.

Another issue, the IMF said, was that digital currencies could mean a country’s citizens have their bank accounts with the central banks directly (as opposed to today, where accounts are held by banks who, in turn, have accounts in central banks). Add to this the concerns of taxation, insolvency laws, and payment systems, and CBDC issuance becomes a “complex legal challenge.”

Have you guys been getting into the IMF polls? 🤣 #Bitcoin pic.twitter.com/6LgWlDYZcZ

— Mags 🟧 (@Crypto_Mags) January 17, 2021

Meanwhile, such issues are not fazing central banks from their CBDC aims. China has been aggressively developing its CBDC since 2015—its digital yuan is currently being extensively tested within the country—while Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and others started such work in 2018-19.

Officials of the US government itself showed interest in developing a state-backed digital dollar last year. But not all countries are excited at the prospects of their own digital currencies.