It’s a sign of the times that government secrecy isn’t top of mind for American activist and whistleblower Chelsea Manning.

“We’re actually so awash in information now that secrecy isn’t the issue anymore,” she said. “It’s verification.”

She spoke to Decrypt over a video call in June about her security work at Web3 privacy project Nym and what brought her—somewhat begrudgingly—back into the world of cryptography.

Manning became synonymous with government transparency when she gave classified documents—250,000 American diplomatic cables and 480,000 Army reports on the Afghanistan and Iraq wars—to WikiLeaks in 2010. It was, and still is, the largest intelligence leak in U.S. history.

In the aftermath, she was court-martialed and served seven years of a 35-year prison sentence before it was commuted by President Barack Obama in 2017. Before the commutation of her sentence, Manning, a transgender woman, was incarcerated at a men’s military prison at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas.

On the day she spoke with Decrypt, it had been a week since British Home Secretary Priti Patel approved the extradition of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to the United States. There he would face charges under the Espionage Act for his role in publishing the documents he received from Manning in 2010.

Manning made it clear that her court martial prevents her from commenting directly on Assange’s extradition. But she did say the prolonged nature of cases like his have sharpened her focus on building tools to help people preserve their privacy.

“I want to ensure that cases that will go on for 12, 15 years don’t happen again in the future,” she said. “Which is why I believe very strongly in these kinds of tools and in this technology. There are pitfalls to not having this kind of technology.”

When she spoke to Decrypt on June 24, it had been a few hours since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. With it, the court eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion and laid the groundwork for bans in as many as 17 states.

The implication of those bans became a very timely example of how people could use a decentralized mixnet like Nym.

Manning explained that someone outside the state of Texas, where an abortion ban has gone into effect, might hypothetically want to offer advice to Texas residents on how or where to safely have the procedure.

To be clear, that’s now illegal in certain jurisdictions.

The would-be helper risks being identified by law enforcement through their Internet metadata. Metadata, while it does not include the content of emails or other messages, could be used to show where the person lives or when and how often they had been in contact with someone in Texas.

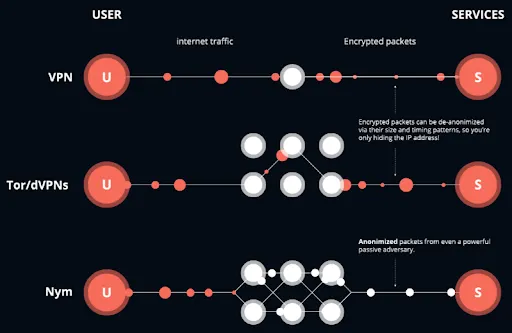

To protect themselves, they could use a VPN, or virtual private network, to route their internet data through an encrypted server. That person could also use something like Tor, a browser that acts like a supercharged VPN by sending data through three different encrypted servers on the way to its destination.

It’s difficult, but not impossible, for encrypted data to be decrypted. There’s where a mixnet, like Nym, comes in, said Manning.

It disaggregates pieces of metadata, like a person’s IP address or the recipient of a message, and mixes it with other metadata. The resulting packets of encrypted data combine the IP addresses, time, date, and location of many different people’s metadata.

It only works if enough node operators participate, breaking apart and remixing packets of metadata. Otherwise it’s like trying to hide in a crowd of only a couple of people.

That’s where the NYM token comes into play. Much like other decentralized, public blockchains, a native token is how Nym incentivizes its users to run nodes and participate on the network. Manning doesn’t have any control over NYM’s tokenomics, but she has worked hard to underscore the importance of the network being both large and decentralized.

“The decentralized network portion is necessary and required in order to have a mixnet,” Manning said. “In order to have the requisite number of nodes operating on the network with enough traffic flow to provide privacy protections on the mix net, you have to incentivize people to run those nodes and incentivize people for validation.”

Manning’s role with the project has been twofold: As a security expert, she’s been figuring out how to overcome hardware issues that have hampered network growth, particularly in rural areas with limited internet access. She’s also been using her connections in the security community to bring privacy advocates back to crypto.

When crypto became short for cryptocurrency instead of cryptography, a lot of the community’s mainstays—herself included—took a step back. It’s a consequence of investors ushering in what she calls “nouveau rich yuppie culture.”

“People laugh, but I’ve lost entire Bitcoins of information that I’ve mined off of a MacBook Pro. So I was very early in this process,” Manning said. “And I moved away from it—I mean, obviously I was in prison for a significant period of time—but even afterwards, I sort of moved away from it because I realized that there’s a lot of people who don’t necessarily understand the technical aspects of this or the security and privacy implications.”