A prominent artist claims that the biggest NFT brand on Earth is secretly run by a conspiracy of Nazi trolls. The artist sold a copycat collection of the brand’s NFTs, netting him some $1.8 million (shared among the four people working on the project). Some called it a clever political statement, others a naked cash grab.

Now the brand is suing the artist, and the implications of the case could be more far-reaching than either party anticipated.

This is the ongoing story of Ryder Ripps, an internet provocateur and conceptual artist who’s done work for Nike and Bruno Mars, and of Yuga Labs, the $4 billion company behind the Bored Ape Yacht Club. When Yuga filed a federal lawsuit against Ripps late last month, the news sent the NFT world into a frenzy—and raised more than a few questions.

Did BAYC’s creators really plant racist easter eggs and hidden Nazi symbols in images touted by the likes of Steph Curry, Jimmy Fallon, and Madonna, or was it all an elaborate troll by a famously attention-seeking artist who once falsely claimed to have redesigned the CIA’s logo?

What’s more, is it a clear case of defamation? And what would a verdict in this case reveal about the still-murky, potentially multi-billion-dollar question of how images associated with NFTs are copyrighted? Also: Can they be copyrighted in the first place?

To legal experts who spoke with Decrypt, the most fascinating element of Yuga’s lawsuit is that it has nothing to do with these questions. Yuga isn’t suing Ripps for defamation nor for copyright infringement. Instead, the multi-billion dollar company is very narrowly accusing Ripps of infringing on the Bored Ape trademark. It may well be that what Yuga isn’t alleging offers more insight into the case and the current state of the NFT industry.

The ‘million-dollar question’

“That’s really important, really kind of unusual, and interesting and unexpected,” University of Kentucky law professor Brian Fyre told Decrypt, speaking about Yuga’s choice to wholly avoid the question of copyright infringement in its lawsuit against Ripps.

Copyright and trademark infringement, though often closely associated, are two very different things. Copyrights protect the content of a work: the plot of a book, the visual elements of a painting, the chorus of a song. Trademarks, on the other hand, safeguard business names, logos, and slogans that constitute a brand. By not pursuing copyright infringement, Yuga is essentially letting slide the fact that Ripps copied thousands of Bored Ape NFT images and sold them for millions of dollars, without changing a pixel. Why?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Zahr Said, associate dean of research at the University of Washington School of Law, told Decrypt.

The answer may lie in the current relationship between companies like Yuga and copyright law.

“Many Bored Ape buyers see ‘IP ownership’ as a big part of the [NFT] value proposition,” said Fyre. Indeed, the last year has seen Bored Ape holders attempt to spin NFTs into unique clothing lines, music groups, burger restaurants, and television shows. Yuga Labs encourages this behavior, and that makes sense: The ethos of NFT communities like BAYC hinges on the presumption that NFT holders are not passive consumers, but active community members wielding varying degrees of control over their purchases.

But recent scholarship suggests that such a copyright structure may be legally dead-on-arrival. In a recent essay, artist and lawyer Dave Steiner laid out a compelling case for how, by giving away rights for each Ape upon purchase, Yuga Labs might be left with no rights to any Apes at all, effectively eliminating most of the company’s value.

Further, because the 10,000 Bored Apes in circulation are almost identical, and often vary by only a single trait, like an earring, the law likely would grant robust copyrights only to owners of the first handful of Bored Apes ever sold, because those images were, at the time, unique.

In Steiner’s interpretation, the law would see every subsequent Bored Ape as some variation of those “originals.” For instance, imagine drawing an earring on an image of Mickey Mouse. That’s not a brand new mouse with full-throated copyright protection. That’s Mickey with an earring. Such a reading of the law would leave the vast majority of Bored Apes, over 99%, effectively worthless in terms of licensing.

Delving into matters of copyright in a courtroom could, therefore, open a Pandora’s Box for Yuga. The issue “introduces a lot of complications that I suspect Yuga didn’t want to deal with right now,” said Fyre.

The same goes for defamation. While Fyre thinks Yuga has more than enough evidence to go after Ripps for defamation, “they didn’t, and I think that was a very wise decision.”

Why? Because in a defamation suit, both sides have access to discovery. Ripps would be granted the legal right to request any number of Yuga’s private correspondences to try and prove his claims that Bored Apes are secretly racist. Even if Ripps is just trolling—and it certainly wouldn’t be the first time—such an opportunity likely would amount to a months-long field day for the artist and his followers, and a never-ending PR nightmare for Yuga.

Two monkeys walk into an NFT marketplace

So, if not for copyright infringement and not for defamation, what’s Yuga suing for?

The company’s lawyers—of Fenwick & West, the prominent Silicon Valley firm known for guiding the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, eBay and Oracle through decades of intellectual property disputes—formally alleged on June, in a suit filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Central California, only that Ripps infringed on Yuga Labs’ trademarks.

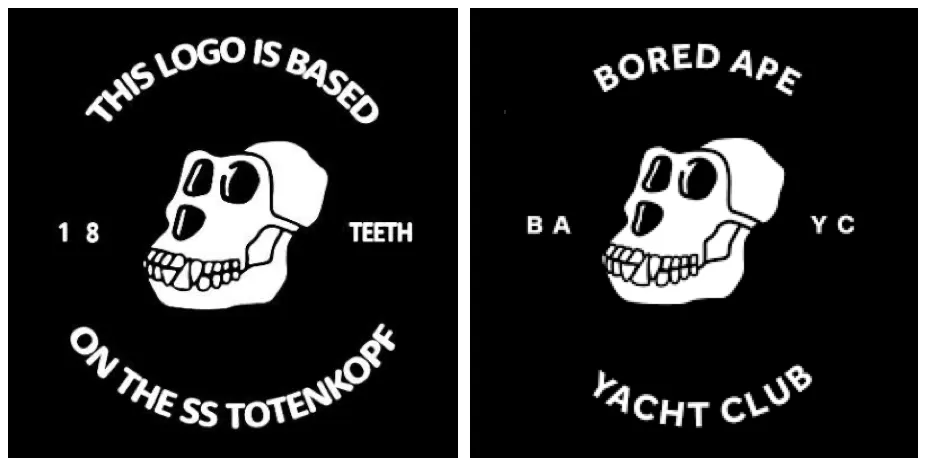

The claim centers on Ripps’ use of the Bored Ape logo and brand. Ripps titled his NFT collection RR/BAYC, promoted an “Ape marketplace” in association with it, and made the collection’s logo a Nazi-inspired riff on the original BAYC logo. Yuga Labs does not yet hold trademarks for the BAYC name and logo, but its applications are pending, permitting it to protect those marks in court.

Yuga’s attorneys will have to prove that by invoking these marks, Ripps created a “likelihood of confusion” for consumers, experts told Decrypt.

“If I were to go out and try to gin up a project that would tick as many boxes of trademark infringement as possible,” said Fyre of Ripps’ collection, “I mean, he did a bang-up job.”

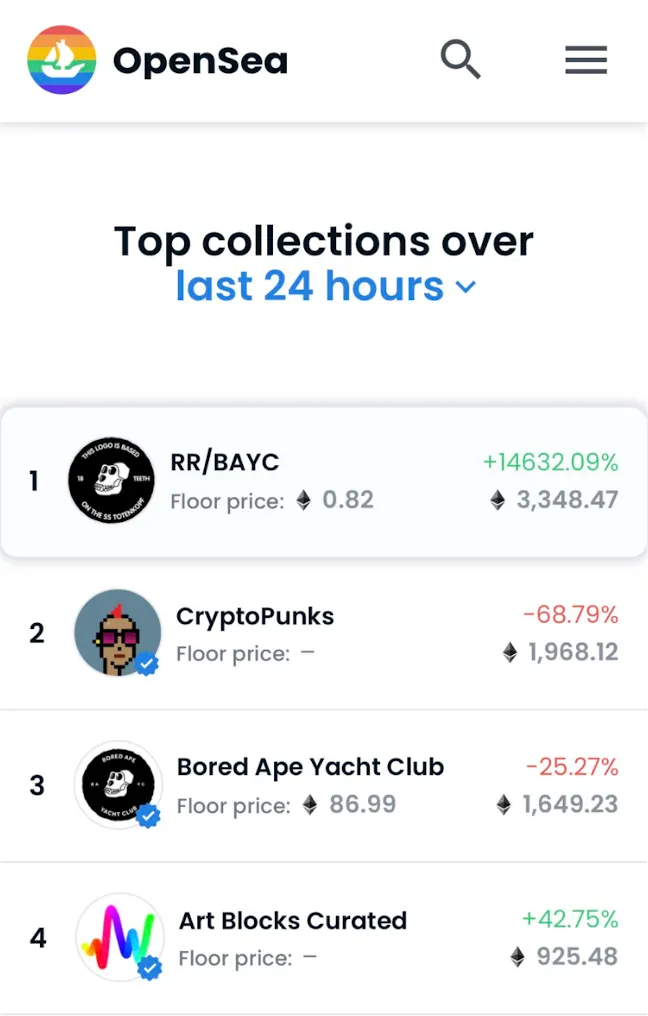

Central to Fyre’s point is that Yuga doesn’t need to prove that every purchaser of an RR/BAYC NFT was hoodwinked into buying a fake ape when they thought they were getting a bonafide Bored Ape. Yuga just needs to show that the value of Ripps’ collection is linked to the value of BAYC.

“You buy a Louis Vuitton knockoff bag for $10 on Canal Street, you know it’s not the real deal, right?” said Fyre. “But the problem is, you’re buying it because of the mark.”

To other legal experts, the fact that Ripps marketed his collection to vocal critics of BAYC, and associated it so closely with claims of Yuga’s alleged racism, could actually work in Ripps’ favor.

“If Ryder can define [his] market as a subset that’s distinct […] that would defeat the claim that the defendant’s work is usurping the market for the original,” explained the University of Washington’s Said. Ripps’ fans hate BAYC, and BAYC holders hate Ripps, and members of one group would never buy NFTs of the other. “I think if they do that successfully, they’re likely off the hook.”

Ripps posted a statement about the lawsuit on Twitter a few days ago. When reached by Decrypt on Sunday and asked whether he’s obtained legal representation, he declined to comment.

— RYDER-RIPPS.ETH 🔜 (@ryder_ripps) June 28, 2022

‘Trying to find leverage’

But even Ripps’ potential trademark infringement may not be all that it seems.

“My big question is: Was this his plan all along?” Fyre asked. “Did he want them to sue him?”

Is getting sued by a $4 billion company the apotheosis of Ripps’ latest meta-conceptual, ironic attention grab? Or a natural consequence of an earnest crusade against a powerful brand? Whatever the motivation behind Ripps’ multi-pronged assault on BAYC, by attempting to quash it with litigation, Yuga Labs may have just exposed itself to another, larger problem.

“Suing is not a very Web3 thing to do,” said Yitzy Hammer, partner at DLT Law, a blockchain legal advisory firm.

Bored Ape Yacht Club is not the first NFT brand to deal with copycats. But it is one of the first to get litigious. Lawsuits, let alone ones this prominent, are rare things in the so-called decentralized and community-minded world of NFT art and Web3 culture.

“A lot of collections, Yuga Labs but also others, accept a lot of infringements where IP lawyers will say that's a very clear infringement,” said Christian Tenkhoff, a partner at law firm Taylor Wessing who specializes in trademarks and Web3. Why? Tenkhoff argues that despite the fact that some NFT owners see IP as a major value proposition, many others in the NFT world believe that “IP is something […] that's old school, that's the old world, that's centralized. And that shouldn’t even happen.”

Yuga, up to now, has taken care to not ruffle the feathers of this vocal faction of the tight-knit Web3 community, the goodwill of which NFT collections depend on, even after Ripps began provoking Yuga in January, with the #BURNBAYC hashtag accumulating a sizable following on Twitter, trending the same week of the RR/BAYC collection’s sellout.

“Ryder Ripps and his community were really pushing them on the white supremacy thing and the Nazi thing, and also [saying] you can’t copy an NFT,” said Hammer. “Just kind of like spitting in their face.”

So, Ripps’ goading may have put Yuga between yet another rock and hard place: continue to let a snowballing faction openly associate their brand with Nazism (during BAYC’s most prominent week of the year, ApeFest, no less), or risk breaking a Web3 norm by involving the federal government.

Only on June 24, days after Ripps’ collection eclipsed the real BAYC to become the top-selling NFT collection in the world on OpenSea, did Yuga finally sue.

“My gut tells me,” said Fyre, “that this lawsuit is more about trying to find leverage to get him to stop trashing their brand than it is any kind of concern about actual trademark infringement issues.”

“I think, you know, in many senses,” Hammer added, “they just felt like they needed to fight back.”

But whatever the motivation, Yuga now finds itself in federal court, arguing about intellectual property. And that fact alone may have forced the company into another corner.

Yuga Labs was born in the experimental, decentralized world of NFTs, but as it now attempts to assert its dominance in the centralized, real-world economy, it may have to pick a lane.

“As these brands go bigger and bigger, they actually need to enforce their trademarks in order to maintain the value within their brands,” said Tenkhoff. “And the tricky part is to get the Web3 space on board and make them see your point.”

Whether or not it was Ripps’ intention, thanks to the artist’s provocations, Yuga Labs may be one of the first major NFT companies to test the balance between honoring the ethos of Web3 and invoking laws to maintain a profitable brand.

“Yuga has to win on two sides here. They have to convince a courtroom, but they also have to convince the public,” said Tenkhoff. “It is so very important that you get the Web3, NFT, and Twitter communities behind you.”